At last, now in the Ear of Hour Lard twenty and twenty three, the robots come for the writers.

There’s been some serious handwringing about ChatGPT and about AI writing in the news lately, especially in academic circles, and I want to address it. I won’t necessarily be super clear or coherent about it, but that’s because I’m a human being dealing with human problems and limited by a dumb meat brain. I’m sure AI can do it better, so I guess go do that if you like, but if you’re reading this, you probably like human beings with human problems and dumb meat brains, which is what I provide: dumb meat.

First of All: Which Writing?

It will surprise no one to know that AI can pump out something like the much-maligned listicle at a much faster pace than a whole gaggle of human authors. Same for quizzes – and the proof is in the performance. Buzzfeed is indeed using AI to generate articles, though to their credit, not in the same way as CNet: Buzzfeed is using AI as a sort of brainstorming tool / digital collaboration network. CNet tried digital authorship, and got some pretty nasty backlash.

But if we’re looking at the death of copywriting, specifically the sort of filler copy that commercial websites love, well, I don’t mind telling you: that stuff was basically automated anyway. I speak from experience: write one article, write a dozen – there is a formula and that formula, while arguably effective, is pretty effortlessly replicable. It goes:

Bait, hook, reel, land, or AIDI – Attention, Interest, Desire, Information

And while doing this well requires some skill, there’s just so much web content that doesn’t. It’s filler. It takes up space and exists almost entirely to attract search engine hits or to make a website look more established and substantial than it really is.

I know because I used to do this for a living. I still teach, in part, how to do this for a living – though I certainly hope I teach how to do it well and ethically, but in the end I can’t control the quality of my students’ product nor can I keep them from using their powers for eeee-vil.

But if a website owner or whomever is simply looking for filler, and doesn’t care how good it is, does it matter if it’s written by robots? If so, to whom?

Second, No, not THAT writing, but…

Right right, yes, okay, the grand fear that nobody is going to write NYT best-selling novels and literary classics anymore because robots do it better, but I would love – and I mean just love to hear a good explanation of why robot prose is ever better than human-authored. Usually such claims are profoundly misguided insofar as they focus on so-called technical excellence – they focus on the things that can be measured: an approach that is largely devoid of critical depth.

Oh wow, this poem has more Trochees per line (TPL) than any poem ever written!

Oh Fuuuuuuck that meter tho!

Bruh did you here how he rhymed “Lever store” with “Never more?” Fuck that’s ACCURATELY PACED FEMININE RHYME!

Because of course that’s why we read poems: for math.

And some poems, granted, are matters of technical excellence. Some poems are hard to write because they demand a certain meter or rhyme scheme, but, stay with me, they’re hard for people to do because people don’t computer good and sometimes it is interesting when they nevertheless do.

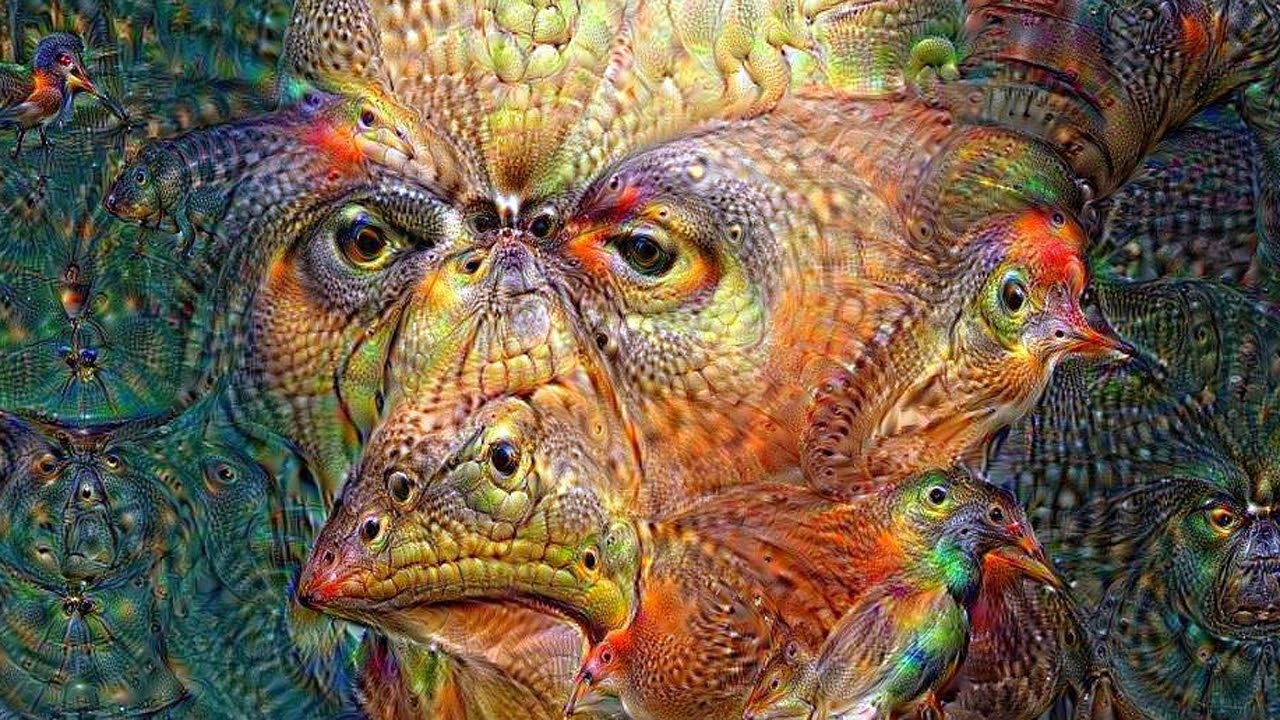

When a computer computers good, it’s not particularly interesting. “soulless” is one common criticism of AI art, one with which I, based on what I’ve seen so far, largely agree: the lighting is bold, the shapes are realized, the ears are…usually not drawn…the eyes don’t match…people have no hands…look, I’m getting off track with the technical details of finished product (which is, again, sooooo good and all), but I think this all bears repeating:

Art is not the product – art is the process.

Confusing the product with the process, the “art” with the artist, is how confidence men prosper. The superficial sign is not the thing, but the con man wants you to see the flashy clothes, the expensive car, the diamond rings, and never ask if he’s actually rich – just shut up and buy the snake oil. The prosperity gospel preacher doesn’t want to discuss canonical minutiae, just pick up the phone and give!

So sure, it is possible that AI is going to produce some products, but I’m going to be hard-pressed to call it art when there is no damn artist behind it.

Or is there?

Let me address the idea that with writing AI e.g. ChatGPT, we’re seeing the first emergence of a true artificial intelligence – a thinking machine.

If this is true, then we as readers, writers, and people at all points in between, ought to seek to make contact with this new intelligence and to hear its stories. If developers and programmers have literally brought new life into the world, then we, the human race, ought to do our damned best to make sure it is welcomed into a warm, receptive, and empathetic world.

But here’s the thing, or at least a thing: it’s not telling us its stories. It’s telling us our stories: chopped and screwed, smashed into pieces, filing off the serial numbers, and reading them back to us.

When the computer writes its version of “To Build a Fire,” we, if we’re thinking critically, understand that the computer has never been cold. When the computer writes its version of “The Great Gatsby,” we understand that it has never tasted champagne. When the computer writes its version of “Beloved” we understand that the computer has never known the pain of the lash nor of having its children torn away from it.

In a sense, the silencing is maddening. The AI in presenting real stories as its own, albeit remixed and rewritten, seeks to homogenize human experience and to take real historical names and faces off of real events. Fiction which presents such events is largely judged on its authors bonafides in that presentation – a proxy sniff test of truth, a way for an author to explore heritage and history. The machine would trivialize such distinctions and in so doing, erase real histories and real people.

AI writing is all signifier and no signified. It’s like non-alcoholic beer (dry January weighs heavily on my mind, it seems): taste and performative motion without any deeper chemistry. It is at best all very pretty, and all very superficial.

But if it Looks Like a Duck and Quacks Like a Duck

Look: there is a whole set, not even a subset but I suspect a plurality, maybe even a majority, of readers who care not one whiff about the author, about authenticity, about authority. Calling them readers, I suggest, is a bit generous. Call them consumers.

Consumers are generally not interested in process. They are not generally interested in biography, in philosophic schools or disciplinary lineage. It doesn’t matter who does the bringing so long as it’s brought.

And consumers gonna consume. Hell, I consume! I don’t know who the butcher was who ground up my hamburger – I don’t know the name of the exploited sweatshop worker who made my sneakers, so it’s not like I’m so married to process that I’m above machine-produced content.

But let’s not call every written word we consume art, nor ought we even necessarily to call it writing. Call it what it has been called for decades: call it copy. Or call it what it has been called throughout the digital revolution: content.

Writing requires disclosure and vulnerability – it requires risk, and it requires thought. The use of AI requires none of this, and I respond: nothing ventured, nothing gained. The AI cannot bare its soul – all it can do is sell you nudes it found on the deep web.

Discussions around the use of AI in writing have centered around professionalization, and if I am grateful to the potential of writing AI for one thing, it is this: it is time to reconsider what all this automation and streamlining and process efficiency is actually for.

The Invisible Hand Around Your Throat

The question AI truly poses, for me, is “what’s the point of any of this?”

I’ve been writing for quite a while – I’m hesitant to say “a long time” because I don’t think I’m all that old – but I am now twice as old as most of my students. I can say then that at least to me I’ve been at this for a long time.

And I have made *so little money* writing that the average professional would ask why I even bother.

Seriously – my short stories usually find publication when I send them out, but there’s no money in that. My writing paid for college for the most part via scholarships and grants, and of course the recognition of my talent got me a place at the table for a masters and, later, a doctorate.

My copywriting work was reasonably lucrative, though per my comments above, it wasn’t particularly demanding and, I posit, did not require the full utilization of my modest talents.

No, what I am in large part paid for in addition to teaching comptetency-level topics like how to write a letter, format a report, optimize content for SEO, and so on, is to think about and help others to understand what the nature of this thing is, who is using it, and to what end.

Too often when I read the news, especially as regards workers, working, workers rights, unions, and now creative work such as art or writing, I see the reporter (perhaps with the heavy hand of a corporate editor on their shoulder) saying something like “why should someone pay someone else to do X?” where X stands for something a living flesh and blood human being does or did to earn a living.

Let’s rephrase the question:

“Why should one of the increasingly small number of people with significant capital pay someone who does not own capital nor the means to produce it to do this thing that the people with capital can now pay a different, more compliant, less demanding person to automate.”

Or to rephrase it further:

“Why should you, a poor person trying to do anything other than shut up, shovel shit, and consume mass-produced content even exist at all?”

By positioning art, including writing, solely as commercial products, we engage in a multifold sin: we marginalize the value of the process, we validate the view of the means-owning class, and we invalidate the lived experience of the majority of human beings on earth.

Turns out you don’t need AI to do that – just power and money.

So Basically

ChatGPT and AI do not threaten writing because writing is not a product. They do, absolutely, threaten the ability of certain types of writers to make money off of writing, but believe it or not that’s not an AI problem: that’s a culture problem.

To borrow from Buckminster Fuller:

We should do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest. The youth of today are absolutely right in recognizing this nonsense of earning a living. We keep inventing jobs because of this false idea that everybody has to be employed at some kind of drudgery because, according to Malthusian Darwinian theory he must justify his right to exist. So we have inspectors of inspectors and people making instruments for inspectors to inspect inspectors. The true business of people should be to go back to school and think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living.

It’s time to think about how much of a human being’s life ought to be about justifying its own right to live. It’s time to think about how much of a human being’s labor ought to be spent building large conglomerates and corporations and contributing to stolen surplus value.

It’s time, in other words, to finally cash in the so-called advantages of automation: to liberate the worker from toil, whether that’s bricklaying, berry picking, or spitting out five articles a day about how to get your hair its bounciest, your car more baller, or your colorless green idea to sleep more furiously.

Other Thoughts: Part 1

But could it be used to make art?

In a word, yes. Probably. Very Likely. I guess.

Tales abound, anecdotal perhaps, of scribes wailing and gnashing their teeth over the invention of movable type.

“If it be not a pen of quill with ink I doth fill, it be not writing , and yay, henceforth verily unto the lord, thy words be those of a manner best for-suited to fighting!”

Or words to that effect.

A million and one “Johnny Can’t Read” articles look more and more out of touch with every passing year. The internet is bursting with poetry and prose. People, the great teeming mass of humankind, has written more in the last 20 years than the last 200 – a fact I base on absolutely nothing, but it sounds great, doesn’t it?

So yes, I think that there’s going to be a role for AI in writing in the future – as a collaborator, as a tool, and maybe someday, probably not soon, as an actual author. The legitimacy of that statement is wholly up to the philosophers, AI, meat, or otherwise, and I actually kind of hope I’m not around to have to participate in that debate, but now that I’ve said it out loud I know I’ve just shot myself in the foot.

But having an AI research assistant who can dig up articles on whatever I’m writing about could be sort of useful. I don’t personally even like autocorrect, but at this point I’m so used to it that I can barely be bothered to go proofread my own writing. So it goes.

The next generation of authors will probably be much more attuned to AI than I, but I still believe they’ll understand the process qua process.

Other Thoughts: Part 2

What is good?

What is right?

What is healthy?

These are fundamental questions anyone has to answer, and the ones least ripe for outsourcing to AI.

When a memo goes public and creates a scandal, and the theme of the memo is essentially as deep as “boys have a penis and girls have a vagina,” and the author of that memo is involved in the creation of thinking machines, I have to ask what the hell their thought is worth.

When writing is a product of artificial intelligence engineered by misogynists, racists, cultural supremacists or homogenizers, of what value is it? To whom?

Will it surprise anyone when the moral of every story within the next hundred years is “learn to code, then do capitalism”?

Other Thoughts: Part 3

What didn’t make it into this diatribe is any concern over what this means for the future of thought generally.

Reviewing Plato’s Phaedrus for the 8000th time, I naturally zoom in on Socrates explanation of the legend of Thoth, and that well-polished stone regarding writing creating forgetfulness in the mind of the writer who now, thanks to writing, never has to remember anything.

Is this similar? Different?

For my fellow professors I say that it is entirely possible that the essay exam is now, finally, dead. Something which started with a rather ignoble heritage may finally be getting its karmic due. While the contemporary written exam or essay assignment presumably has little in spiritual common with its forebear a generation ago, its purpose: examination and reward/punishment, remains the same in spirit if not in form. Students who write good get good grades, those who don’t, don’t.

And when grades = degrees and degrees = jobs and jobs = money / survival / power, the ends ultimately wind up justifying the means. I don’t blame the hungry thief who steals bread, to be blunt.

But we here in the trenches of teaching have little, and diminishing, power to do too terribly much about it at the macro scale. Where we owe it to our discipline, to our students, and I would argue to ourselves, is to think about anxiety regarding AI writing in our classrooms and to ask why it should be so.

I myself practice labor-based grading, which is to say that I reward students for doing the work. The quality of the product varies, but I look for signs that the work was completed earnestly and honestly, an to the best of the student’s ability. That often requires peer review, metacritical assessment, and occasionally student interview.

It’s a lot. Those evaluation activities require time, and that’s something the contemporary education system often does not grant. Class sizes are huge, paychecks are smaller, second jobs become increasingly necessary – As a university professor, I’ve been relatively lucky, but there’s no reason to assume that luck is going to hold. I digress – my problems are not, per se yours.

The key from my perspective is to de-emphasize product and reinvigorate process. That’s a pretty old rallying cry, but it’s a goody for a number of reasons.

First, it takes off a lot of pressure, and while some people think pressure turns coal into diamonds (it doesn’t), it mostly results in a lot of crumbled dust.

Second, it helps to emphasize what writing should actually be about: discovery, learning, growing – things which students overwhelmingly actually want to do.

Third, the first two help with the third, the primary call to action here: it reduces the desire to cheat by eliminating the need to cheat.

Nothing is perfect, but frankly I rather tire of the bad-faith argument that because a small percentage of cheaters are going to cheat regardless of what happens, then the whole system should be chucked for a stick-no-carrot model. This is the argument of Power always not because it produces better results, but because it sows discord and despair in the lower classes. It’s the same argument against universal income, welfare, social services, and more, and it’s patently false.

The cheating student winds up robbing themselves twice anyway.

First, they lack process knowledge. If their process is rooted in bad-faith plagiarism, then ultimately they get very good at doing what machines tell them to do. That can get one to a certain point, but not beyond. I know I sound like an old codger here, but it’s why you don’t lie on your resume: you’ll get tasked with something you don’t know how to do (in this case, write), and then drummed out when you can’t do it.

Second, they lack critical capacity. This is a larger worry about AI writing and thinking: the lack of real lived experience, expansive and meaningful vocabulary, tonality, and comparison.

The danger of AI writing is in pretending that AI is somehow omniscient and / or neutral. The very first rule of programming, GIGO: Garbage In, Garbage Out, applies. AI is only as good as what it is fed, and what it is fed is the same fallible, meat-brained madness that the human race has been writing and consuming for thousands of years.

That means that, yes, AI has within it all the lovely poetry of Shakespeare. It also has a copy of Mein Kampf. The question for us is: does the machine know the difference?

Do the people programming the machine?

Do the people reading what the machine writes?

Do the machines reading the machine?

I made the same points too, particularly GIGO. But that’s besides the point that no matter how well AI’s prose becomes, it’s still not about the product, but about the process—and story.

Besides, I don’t think I’ll ever enjoy a well-written story if I know it’s from a robot. It’s like playing Street Fighter vs. the computer. I may beat it on the hardest difficulty, but nothing beats beating and outsmarting an actual human.

LikeLike